Vesyegonsky district. Settlements of Veseyegonsky district An excerpt characterizing Veseyegonsky district

And provinces - in the north, - in the west and - in the east.

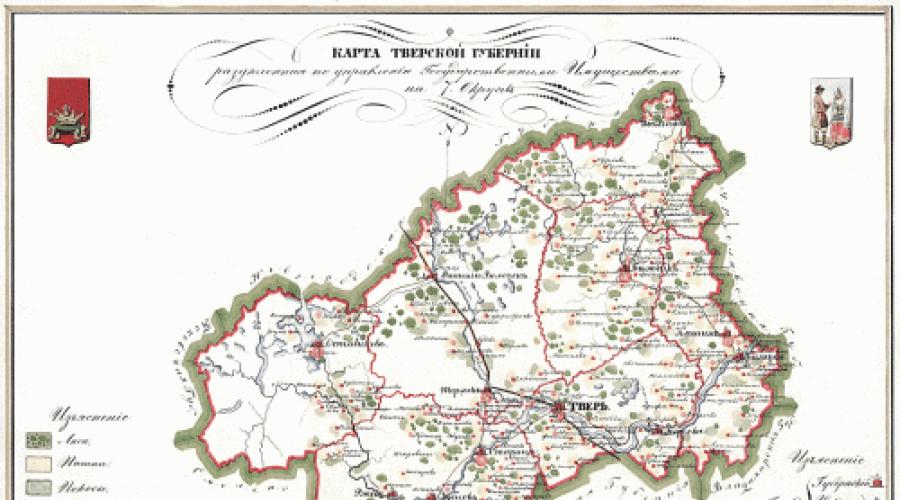

The Tver province was formed in 1796 on the site of the Tver governorship, established on November 25, 1775. The center of the province was the city of Tver.

At the time of its formation, the Tver province included 9 districts: Bezhetsky, Vyshnevolotsky, Zubtsovsky, Kashinsky, Novotorzhsky, Ostashkovsky, Rzhevsky, Staritsky, Tverskoy. In 1803, the districts that were abolished during the formation of the province were recreated: Vesyegonsky, Kalyazinsky and Korchevsky.

From 1803 to 1918, the Tver province included 12 districts:

| № | County | County town | Area, verst | Population (1897), people |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bezhetsky | Bezhetsk (9,450 people) | 7 371,5 | 247 952 |

| 2 | Vesyegonsky | Vesyegonsk (3,457 people) | 6 171,1 | 155 431 |

| 3 | Vyshnevolotsky | Vyshny Volochek (16,612 people) | 8 149,4 | 179 141 |

| 4 | Zubtsovsky | Zubtsov (2,992 people) | 2 610,2 | 103 109 |

| 5 | Kalyazinsky | Kalyazin (5,496 people) | 2 703,7 | 111 807 |

| 6 | Kashinsky | Kashin (7,544 people) | 2 622,5 | 119 510 |

| 7 | Korchevskaya | Korcheva (2,384 people) | 3 810,9 | 119 009 |

| 8 | Novotorzhsky | Torzhok (12,698 people) | 4 602,4 | 146 178 |

| 9 | Ostashkovsky | Ostashkov (10,445 people) | 7 623,6 | 130 161 |

| 10 | Rzhevsky | Rzhev (21,265 people) | 3 713,9 | 143 789 |

| 11 | Staritsky | Staritsa (6,368 people) | 3 963,1 | 146 143 |

| 12 | Tverskaya | Tver (53,544 people) | 3 494,7 | 166 905 |

On December 28, 1918, Kimry district was formed, on January 10, 1919 - Krasnokholmsky district. On May 20, 1922, the Zubtsovsky, Kalyazinsky and Korchevsky districts were abolished, and the Vesyegonsky and Krasnokholmsky districts were transferred to the Rybinsk province (but already in 1923 they were returned back to the Tver province). In 1924, Krasnokholmsky and Staritsky districts were abolished, and in 1927 - Kashinsky.

On January 14, 1929, the Tver province was liquidated; its territory is divided between the Moscow and Western regions.

Additional materials on the Tver province

- Maps of districts of the Tver province

Maps of the districts of the Tver province were compiled by the Provincial Statistical Bureau based on research data from 1886-90 and 1915. The exact date of compilation of the maps is not known. Maps of the districts of the Tver province are compiled on a scale of 5 versts per inch. The maps show: settlements (indicating the number and living population), gatehouses, estates, hamlets, villages and graveyards, factories, factories, mills and other objects. The maps show the boundaries: provincial, district and volost.Maps of districts of the Tver province:  Download the map of Tverskoy district

Download the map of Tverskoy district

Conventional signs

- Lists of populated places of the Russian Empire, compiled and published by the Central Statistical Committee of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. - St. Petersburg: in the printing house of Karl Wulff: 1861-1885.

Tver province: according to information from 1859 / processed by ed. I. Wilson. - 1862. - XL, 454 pp., l. color kart. Download . - Map of the Tver province: [general geographical folding map]. - , in English inch 20 versts. - [Tver: b. i., 1913]. - 1 to. ; 44 x 62. Download.

- Map of the Tver province: With the boundaries of volosts, parishes, camps, conscription areas for military service, zemstvo schools, postal and trade routes, postal and zemstvo stations / Comp. Tver lips. zemstvo council. — St. Petersburg: Cartogr. manager A. Ilyina: 1879. - 1 volume (2 sheets): color; 76x46 (87x68). Scale: 10 versts per inch.

And the RSFSR. The county town is Vesyegonsk.

In 1890, the population in the district, excluding cities, was 146,225 (67,653 m and 78,572 women), including 25 thousand Karelians. 98.75% of the population are Orthodox. Population density varies: 59 women. per 1 sq. V. in the vicinity of the city of Kr. Holm and 8 to the west. (in Zamolozhye) and in the north-east of the district. The vast majority of the inhabitants of the district are peasants, of whom there are 51,941 revision souls, including the former. landowner 21166, ex. Kaz. 21988 ex. beat 6873, personal 199 and landless 715 rev. settlements: 2 cities (Vesyegonsk and the provincial Krasny Kholm), 1 monastery (Krasnokholmsky Anthony's husband, 2 versts from Krasny Kholm), 65 villages, 14 graveyards, 58 villages, 111 estates and 802 villages. There are no large non-urban settlements.

At the end of the 19th century, there were 24,347 peasant households in the district, including 2,421 Bobyl households. Convenient lands belonged to 47% of the cross. in the allotment, 7.4 cross. owners, 28.2 nobles, 7.1 treasury, 4.9 appanage, 3.1 merchants. and 2.3% others. owners. Manor and arable land amounted to 141,242 dessiatines. (including 125 thousand dessiatines in the allotment of the cross), or 1/4 of the total area of convenient land. The main occupation of the population is agriculture; the latter, by the end of the 19th century, could not satisfy all the needs of the population; bread had to be purchased up to 15 thousand quarters a year. There are 34,047 horses, 49,493 cows, and 64,838 small livestock. Local trades: cutting and rafting of timber, fishing on the Mologa River; artisanal: tar smoking in Zamolozhye (320 people), gvozdarny in Peremutskaya parish. to the north-east (852 people), leather (300 people) and shoemaking (1500 hours, 210 thousand rubles) in the vicinity of the city of Kr. Hill; latrines: agriculture (in Yaroslavl), shipping, fulling and wool cutting, unskilled laborer; passports were taken in 1886 - 15,648. There were 57 factories and factories in the district (except for cities) in 1886; their production costs 357 thousand rubles; including 2 distilleries. plant (for 122 thousand rubles), 1 flour. mill (134 tr.), 16 cheeses. and dairy factories (9 thousand poods, 65 thousand rubles). There are 22 fairs. Trading points: Krasny Kholm, the villages of Kesma, Sushigoritsy, Smerdyn. Public schools in the county: parish church. 7, zemstvo 45, private 1, school. literacy - 24. Students in 1889 - 90: boys. 3256, dev. 641. Zemstvo spends (1891) 22,050 rubles on schools. There are three hospitals - all zemstvo (in Vesyegonsk, Krasny Kholm and in the village of Sushigoritsy); The zemstvo spends (1888) 25,821 rubles on medical services. Zemstvo income in 1888 - 128,368 rubles. .

During 1918, due to the reduction in the number of villages in Volodinskaya, Prudskaya, Topalkovskaya, Chistinskaya volosts, Pokrovo-Konoplinskaya, Polyanskaya, Rachevskaya and Yuryevskaya volosts were formed. At the same time, part of the new and old volosts entered the newly formed Krasnokholmsky district. It was also planned to create the Bratkovskaya volost from part of the villages of Martynovskaya, but this decision of the local authorities was not approved by the NKVD.

The resolution of the NKVD dated January 10, 1919 approved the transfer of the Antonovskaya, Volodinskaya, Deledinskaya, Polyanskaya, Popovskaya, Prudskaya, Putilovskaya, Rachevskaya, Khabotskaya, Chistinskaya and Yuryevskaya volosts to the newly formed Krasnokholmsky district, and the decree of March 27, 1920 - the Martynovskaya volost.

In 1919 - 1920, the borders of Vesyegonsky with the Cherepovets district of the Cherepovets province and the Mologa district of the Yaroslavl province were clarified. As a result, a number of wastelands were transferred to the Yaroslavl province; wastelands, dachas, and also villages were included in Tverskaya province: Elizovo, Zheltikha, Chupino.

By a decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of April 15, 1921, the district, consisting of 15 volosts, was transferred to the Rybinsk province, and by a decree of February 15, 1923, it was returned to Tverskaya, but already consisting of 13 volosts: Lopatinskaya and Mikhailovskaya volosts had previously become part of the Vyshnevolotsk district (resolution of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee dated June 22, 1922).

By a resolution of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of March 3, 1924, in connection with the liquidation of the Krasnokholmsky district, the Martynovskaya volost was returned to the Vesyegonsky district.

By a resolution of the Tver Provincial Executive Committee of March 28, 1924, the Arkhanskaya, Zaluzhskaya, Makarovskaya, Martynovskaya, Nikolskaya, Peremutskaya, Pokrovo-Konoplinskaya, Telyatinskaya, Shcherbovskaya volosts were liquidated. Their villages were included in the enlarged Kesemskaya, Lukinskaya, Topalkovskaya and Chamerovskaya volosts, as well as in the newly formed Vesyegonskaya and Sandovskaya.

As part of the Russian Empire and the RSFSR. The county town is Vesyegonsk.

Geography

Population

In 1890, the population in the district, excluding cities, was 146,225 (67,653 m and 78,572 women), including 25 thousand Karelians. 98.75% of the population are Orthodox. Population density varies: 59 women. per 1 sq. V. in the vicinity of the city of Kr. Holm and 8 to the west. (in Zamolozhye) and in the north-east of the district. The vast majority of the inhabitants of the district are peasants, of whom there are 51,941 revision souls, including the former. landowner 21166, ex. Kaz. 21988 ex. beat 6873, personal 199 and landless 715 rev. settlements: 2 cities (Vesyegonsk and the provincial Krasny Kholm), 1 monastery (Krasnokholmsky Anthony's husband, 2 versts from Krasny Kholm), 65 villages, 14 graveyards, 58 villages, 111 estates and 802 villages. There are no large non-urban settlements.

Economy

At the end of the 19th century, there were 24,347 peasant households in the district, including 2,421 Bobyl households. Convenient lands belonged to 47% of the cross. in the allotment, 7.4 cross. owners, 28.2 nobles, 7.1 treasury, 4.9 appanage, 3.1 merchants. and 2.3% others. owners. Manor and arable land amounted to 141,242 dessiatines. (including 125 thousand dessiatines in the allotment of the cross), or 1/4 of the total area of convenient land. The main occupation of the population is agriculture; the latter, by the end of the 19th century, could not satisfy all the needs of the population; bread had to be purchased up to 15 thousand quarters a year. There are 34,047 horses, 49,493 cows, and 64,838 small livestock. Local trades: cutting and rafting of timber, fishing on the Mologa River; artisanal: tar smoking in Zamolozhye (320 people), gvozdarny in Peremutskaya parish. to the north-east (852 people), leather (300 people) and shoemaking (1500 hours, 210 thousand rubles) in the vicinity of the city of Kr. Hill; latrines: agriculture (in Yaroslavl), shipping, fulling and wool cutting, unskilled laborer; passports were taken in 1886 - 15,648. There were 57 factories and factories in the district (except for cities) in 1886; their production costs 357 thousand rubles; including 2 distilleries. plant (for 122 thousand rubles), 1 flour. mill (134 tr.), 16 cheeses. and dairy factories (9 thousand poods, 65 thousand rubles). There are 22 fairs. Trading points: Krasny Kholm, the villages of Kesma, Sushigoritsy, Smerdyn. Public schools in the county: parish church. 7, zemstvo 45, private 1, school. literacy - 24. Students in 1889 - 90: boys. 3256, dev. 641. Zemstvo spends (1891) 22,050 rubles on schools. There are three hospitals - all zemstvo (in Vesyegonsk, Krasny Kholm and in the village of Sushigoritsy); The zemstvo spends (1888) 25,821 rubles on medical services. Zemstvo income in 1888 - 128,368 rubles. .

Administrative division

- Antonovskaya, center - village. Antonovskoe.

- Arkhanskaya - village Arkhanskoe.

- Volodinskaya - Pronino village.

- Deledinskaya - s. Deledino.

- Zaluzhskaya - village Zaluzhye.

- Kesemskaya - village Kesma.

- Lopatinskaya - village Lopatikha.

- Lukinskaya - village Lukino.

- Lyubegoshskaya - village Lyubegoschi.

- Makarovskaya - village Makarovo.

- Martynovskaya - village Martynovo.

- Mikhailovskaya - Monakovo village.

- Nikolskaya - Polonskoye village.

- Peremutskoye - village of Peremut.

- Popovskaya - village Turkova.

- Prudskaya - village Ostashevo.

- Putilovskaya - village Putilovo.

- Telyatinskaya - village Ivan-Pogost.

- Topalkovskaya - village Topalki.

- Khabotskaya - s. Khabotskoe.

- Chamerovskaya - village Chamerovo.

- Chistinskaya - village Clean.

- Shcherbovskaya - village Shcherbovo.

In terms of police, the county was divided into four camps:

- 1st camp, stanovoy apartment with. Kesma.

- 2nd camp, camp apartment, Krasny Holm.

- 3rd Stan, Stanovaya apartment with. Svishchevo.

- 4th Stan, Stanovaya apartment with. Sandovo.

During 1918, due to the reduction in the number of villages in Volodinskaya, Prudskaya, Topalkovskaya, Chistinskaya volosts, Pokrovo-Konoplinskaya, Polyanskaya, Rachevskaya and Yuryevskaya volosts were formed. At the same time, part of the new and old volosts entered the newly formed Krasnokholmsky district. It was also planned to create the Bratkovskaya volost from part of the villages of Martynovskaya, but this decision of the local authorities was not approved by the NKVD.

The resolution of the NKVD dated January 10, 1919 approved the transfer of the Antonovskaya, Volodinskaya, Deledinskaya, Polyanskaya, Popovskaya, Prudskaya, Putilovskaya, Rachevskaya, Khabotskaya, Chistinskaya and Yuryevskaya volosts to the newly formed Krasnokholmsky district, and the decree of March 27, 1920 - the Martynovskaya volost.

In 1919 - 1920, the borders of Vesyegonsky with the Cherepovets district of the Cherepovets province and the Mologa district of the Yaroslavl province were clarified. As a result, a number of wastelands were transferred to the Yaroslavl province; wastelands, dachas, and also villages were included in Tverskaya province: Elizovo, Zheltikha, Chupino.

By a decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of April 15, 1921, the district, consisting of 15 volosts, was transferred to the Rybinsk province, and by a decree of February 15, 1923, it was returned to Tverskaya, but already consisting of 13 volosts: Lopatinskaya and Mikhailovskaya volosts had previously become part of the Vyshnevolotsk district (resolution of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee dated June 22, 1922).

By a resolution of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of March 3, 1924, in connection with the liquidation of the Krasnokholmsky district, the Martynovskaya volost was returned to the Vesyegonsky district.

By a resolution of the Tver Provincial Executive Committee of March 28, 1924, the Arkhanskaya, Zaluzhskaya, Makarovskaya, Martynovskaya, Nikolskaya, Peremutskaya, Pokrovo-Konoplinskaya, Telyatinskaya, Shcherbovskaya volosts were liquidated. Their villages were included in the enlarged Kesemskaya, Lukinskaya, Topalkovskaya and Chamerovskaya volosts, as well as in the newly formed Vesyegonskaya and Sandovskaya.

By a resolution of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of October 3, 1927, the Lopatinsky and Pestovsky village councils of the Lukinsky volost were transferred to the Vyshnevolotsky district.

Current situation

Currently, the territory of the county (within the boundaries of 1917) is part of the Vesyegonsky, Sandovsky, Krasnokholmsky, Molokovsky and Lesnoy districts of the Tver region, as well as the Pestovsky district of the Novgorod region.

Write a review about the article "Vesyegonsky district"

Notes

Links

- // Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron: in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additional). - St. Petersburg. , 1890-1907.

|

||||||||

An excerpt characterizing Vesyegonsky district

“I saw it myself,” said the orderly with a self-confident grin. “It’s time for me to know the sovereign: it seems like how many times I’ve seen something like this in St. Petersburg.” A pale, very pale man sits in a carriage. As soon as the four blacks let loose, my fathers, he thundered past us: it’s time, it seems, to know both the royal horses and Ilya Ivanovich; It seems that the coachman does not ride with anyone else like the Tsar.Rostov let his horse go and wanted to ride on. A wounded officer walking past turned to him.

-Who do you want? – asked the officer. - Commander-in-Chief? So he was killed by a cannonball, killed in the chest by our regiment.

“Not killed, wounded,” another officer corrected.

- Who? Kutuzov? - asked Rostov.

- Not Kutuzov, but whatever you call him - well, it’s all the same, there aren’t many alive left. Go over there, to that village, all the authorities have gathered there,” said this officer, pointing to the village of Gostieradek, and walked past.

Rostov rode at a pace, not knowing why or to whom he would go now. The Emperor is wounded, the battle is lost. It was impossible not to believe it now. Rostov drove in the direction that was shown to him and in which a tower and a church could be seen in the distance. What was his hurry? What could he now say to the sovereign or Kutuzov, even if they were alive and not wounded?

“Go this way, your honor, and here they will kill you,” the soldier shouted to him. - They'll kill you here!

- ABOUT! what are you saying? said another. -Where will he go? It's closer here.

Rostov thought about it and drove exactly in the direction where he was told that he would be killed.

“Now it doesn’t matter: if the sovereign is wounded, should I really take care of myself?” he thought. He entered the area where most of the people fleeing from Pratsen died. The French had not yet occupied this place, and the Russians, those who were alive or wounded, had long abandoned it. On the field, like heaps of good arable land, lay ten people, fifteen killed and wounded on every tithe of space. The wounded crawled down in twos and threes together, and one could hear their unpleasant, sometimes feigned, as it seemed to Rostov, screams and moans. Rostov started to trot his horse so as not to see all these suffering people, and he became scared. He was afraid not for his life, but for the courage that he needed and which, he knew, would not withstand the sight of these unfortunates.

The French, who stopped shooting at this field strewn with the dead and wounded, because there was no one alive on it, saw the adjutant riding along it, aimed a gun at him and threw several cannonballs. The feeling of these whistling, terrible sounds and the surrounding dead people merged for Rostov into one impression of horror and self-pity. He remembered his mother's last letter. “What would she feel,” he thought, “if she saw me now here, on this field and with guns pointed at me.”

In the village of Gostieradeke there were, although confused, but in greater order, Russian troops marching away from the battlefield. The French cannonballs could no longer reach here, and the sounds of firing seemed distant. Here everyone already saw clearly and said that the battle was lost. Whoever Rostov turned to, no one could tell him where the sovereign was, or where Kutuzov was. Some said that the rumor about the sovereign’s wound was true, others said that it was not, and explained this false rumor that had spread by the fact that, indeed, the pale and frightened Chief Marshal Count Tolstoy galloped back from the battlefield in the sovereign’s carriage, who rode out with others in the emperor’s retinue on the battlefield. One officer told Rostov that beyond the village, to the left, he saw someone from the higher authorities, and Rostov went there, no longer hoping to find anyone, but only to clear his conscience before himself. Having traveled about three miles and having passed the last Russian troops, near a vegetable garden dug in by a ditch, Rostov saw two horsemen standing opposite the ditch. One, with a white plume on his hat, seemed familiar to Rostov for some reason; another, unfamiliar rider, on a beautiful red horse (this horse seemed familiar to Rostov) rode up to the ditch, pushed the horse with his spurs and, releasing the reins, easily jumped over the ditch in the garden. Only the earth crumbled from the embankment from the horse’s hind hooves. Turning his horse sharply, he again jumped back over the ditch and respectfully addressed the rider with the white plume, apparently inviting him to do the same. The horseman, whose figure seemed familiar to Rostov and for some reason involuntarily attracted his attention, made a negative gesture with his head and hand, and by this gesture Rostov instantly recognized his lamented, adored sovereign.

“But it couldn’t be him, alone in the middle of this empty field,” thought Rostov. At this time, Alexander turned his head, and Rostov saw his favorite features so vividly etched in his memory. The Emperor was pale, his cheeks were sunken and his eyes sunken; but there was even more charm and meekness in his features. Rostov was happy, convinced that the rumor about the sovereign’s wound was unfair. He was happy that he saw him. He knew that he could, even had to, directly turn to him and convey what he was ordered to convey from Dolgorukov.

But just as a young man in love trembles and faints, not daring to say what he dreams of at night, and looks around in fear, looking for help or the possibility of delay and escape, when the desired moment has come and he stands alone with her, so Rostov now, having achieved that , what he wanted more than anything in the world, did not know how to approach the sovereign, and he was presented with thousands of reasons why it was inconvenient, indecent and impossible.

"How! I seem to be glad to take advantage of the fact that he is alone and despondent. An unknown face may seem unpleasant and difficult to him at this moment of sadness; Then what can I tell him now, when just looking at him my heart skips a beat and my mouth goes dry?” Not one of those countless speeches that he, addressing the sovereign, composed in his imagination, came to his mind now. Those speeches were mostly held under completely different conditions, they were spoken for the most part at the moment of victories and triumphs and mainly on his deathbed from his wounds, while the sovereign thanked him for his heroic deeds, and he, dying, expressed his love confirmed in fact my.

“Then why should I ask the sovereign about his orders to the right flank, when it is already 4 o’clock in the evening and the battle is lost? No, I definitely shouldn’t approach him. Shouldn't disturb his reverie. It’s better to die a thousand times than to receive a bad look from him, a bad opinion,” Rostov decided and with sadness and despair in his heart he drove away, constantly looking back at the sovereign, who was still standing in the same position of indecisiveness.

While Rostov was making these considerations and sadly driving away from the sovereign, Captain von Toll accidentally drove into the same place and, seeing the sovereign, drove straight up to him, offered him his services and helped him cross the ditch on foot. The Emperor, wanting to rest and feeling unwell, sat down under an apple tree, and Tol stopped next to him. From afar, Rostov saw with envy and remorse how von Tol spoke for a long time and passionately to the sovereign, and how the sovereign, apparently crying, closed his eyes with his hand and shook hands with Tol.

“And I could be in his place?” Rostov thought to himself and, barely holding back tears of regret for the fate of the sovereign, in complete despair he drove on, not knowing where and why he was going now.

His despair was the greater because he felt that his own weakness was the cause of his grief.

He could... not only could, but he had to drive up to the sovereign. And this was the only opportunity to show the sovereign his devotion. And he didn’t use it... “What have I done?” he thought. And he turned his horse and galloped back to the place where he had seen the emperor; but there was no one behind the ditch anymore. Only carts and carriages were driving. From one furman, Rostov learned that the Kutuzov headquarters was located nearby in the village where the convoys were going. Rostov went after them.

The guard Kutuzov walked ahead of him, leading horses in blankets. Behind the bereytor there was a cart, and behind the cart walked an old servant, in a cap, a sheepskin coat and with bowed legs.

- Titus, oh Titus! - said the bereitor.

- What? - the old man answered absentmindedly.

- Titus! Go threshing.

- Eh, fool, ugh! – the old man said, spitting angrily. Some time passed in silent movement, and the same joke was repeated again.

At five o'clock in the evening the battle was lost at all points. More than a hundred guns were already in the hands of the French.

Przhebyshevsky and his corps laid down their weapons. Other columns, having lost about half of the people, retreated in frustrated, mixed crowds.

The remnants of the troops of Lanzheron and Dokhturov, mingled, crowded around the ponds on the dams and banks near the village of Augesta.

At 6 o'clock only at the Augesta dam the hot cannonade of the French alone could still be heard, who had built numerous batteries on the descent of the Pratsen Heights and were hitting our retreating troops.

In the rearguard, Dokhturov and others, gathering battalions, fired back at the French cavalry that was pursuing ours. It was starting to get dark. On the narrow dam of Augest, on which for so many years an old miller sat peacefully in a cap with fishing rods, while his grandson, rolling up his shirt sleeves, was sorting out silver quivering fish in a watering can; on this dam, along which for so many years the Moravians drove peacefully on their twin carts loaded with wheat, in shaggy hats and blue jackets and, dusted with flour, with white carts leaving along the same dam - on this narrow dam now between wagons and cannons, under the horses and between the wheels crowded people disfigured by the fear of death, crushing each other, dying, walking over the dying and killing each other only so that, after walking a few steps, to be sure. also killed.

Tverskaya estate VESYEGONSKY DISTRICT

.

- List of nobles living in Vesyegonsky district and owning real estate. 1809 - GATO. F. 645. Op. 1. D. 5166. L. 78 - 91.

- General track record of the nobles of the Vesyegonsky district. 1817 - GATO. F. 645. Op. 1. D. 5166. L. 216-258.

- General track record of the nobles of the Vesyegonsky district. 1821.- GATO. F. 645. Op. 1. D. 5166. L. 263-317.

- About the riots that took place at the Vesyegonsky district meeting of the noble nobility. Aug 15 1860 - GATO. F. 59. Op. 1. D. 3912. 45 l.

- Information about industrial and commercial establishments located in the estates of Vesegonsk landowners. 1866 - GATO. F. 795. Op. 1. D. 12. L. 5-12, 15-38.

In total, there are 160 estates in the county and 87 industrial establishments.

- List of hereditary nobles of the Vesyegonsky district who have the right to participate in the noble assembly, indicating their rank, amount of land, education. 1889 - GATO. F. 645. Op. 1. D. 6925. L. 1-3 vol.

- Map of Vesyegonsky district. 1894 - GATO. F. 800. Op. 1. D. 13856. L. 1.

Estates are marked on the map.

- List of nobles of Vesyegonsky district. 1893-1895 - GATO. F. 645. Op. 1. D. 6959. L. 1-9 vol.

- Information about the property under the jurisdiction of the Vesyegonsk noble guardianship due to the lack of heirs. Apr 20 1895 - GATO. F. 59. Op. 1. D. 5288. L. 118.

- Map of Vesyegonsky district. 1913 - GATO. F. 800. Op. 1. D. 13856. L. 2.

Estates are marked on the map.

- List of landowners of Vesyegonsky district indicating the amount of land they own in this district. B. d. - GATO. F. 795. Op. 1. D. 1479. 46 l.

- Shubinsky S.N. Second Lieutenant Fedoseev // Shubinsky S.N. Historical essays and stories. - St. Petersburg: Type. Suvorin, 1903.- P. 460-470.

About the detention in 1797 of the noble assessor of the Vesyegonsky court, second lieutenant Maslov, of second lieutenant Fedoseev, who pretended to be sent by imperial command for a census of landowner peasants in order to establish new quitrent rates. The estates of Batyushkov, Sysoev, Zherebtsova, Ukhtomsky, Snoksarev and others are mentioned.

- A list of former landowners who were left within the boundaries of their estates or who received land for labor use outside of them. .- GATO.- F. R- 835.- Op. 8.- D. 207.- L. 55 vol.

- Response of the head of the Vesyegonsk Museum A. Vinogradov to the attitude of the Gubernia Museum dated April 19. 1923, with a list of estates by volost and brief reports on the seizure of individual museum valuables. May 8, 1923 - GATO.- F. R- 488.- Op. 5.- D. 42.- L. 26-27.

- Minutes No. 1 of the meeting of the county commission to consider the rights of former landowners living on their former estates to land use on the basis of the Decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of March 20, 1925, August 11. 1925 - GATO.- F. R- 835.- Op. 9.- D. 207.- L. 253-254.

- List of items included in state land property from those seized from former landowners and other non-labor land users in the period from July 29, 1925 until the end of the work of the Special Commissions for Confiscation. 9 Sep. 1926 - Ibid. - D. 206, vol. 2. - L. 683. - Lists of former landowners and large landowners of Vesyegonsky district. subject to eviction, and the report of the UZU on their eviction. 1927 - GATO.- F. R- 835.- Op. 11.- D. 147.- 9 l.

- Local history dictionary of the Vesyegonsky district of the Tver region / Compiled by G.A. Larin; ed. D.V. Kupriyanov. - Tver, 1994. - 150 p.

- Compiled on the basis of Art. 35-37. Regulations on zemstvo institutions in their final form, a list of persons entitled to participate in the Vesyegonsky district. in the 1st zemstvo electoral assembly for the selection of district zemstvo councilors for three years from 1900: Nobles // Tver. lips Gazette.- 1900.- June 8 (N 62).- P. 1.

There are 65 names on the list.

- Compiled on the basis of Art. 35-37. Regulations on zemstvo institutions in their final form, a list of persons entitled to participate in the Vesyegonsky district. in the 1st Zemstvo Electoral Congress for the election of representatives to the 1st Zemstvo Electoral Assembly: Nobles // Tver. lips Gazette.- 1900.- June 8 (N 62).- P. 2.

There are 17 names on the list.

- List of vowels of the Vesyegonsky district zemstvo assembly for the third year since 1900 // Tver. lips Gazette.- 26 Aug. (N 96).- P. 2.

- List of estates belonging to Vseyegonsk landowners and subject to sale at public auction for non-payment of arrears of the zemstvo tax for over one and a half, two, three or more years // Tver. lips Gazette. - 1903. - June (Appendix to N 57, 58, 59).

- List of persons entitled to participate in electoral meetings for the selection of zemstvo councilors in 1900, according to Vesyegonsky district. // Tver. lips Gazette.- 1900.- February 17. (N 20).- P. 1-2.

The list contains the surnames, first names, patronymics and titles of nobles, the amount of land and the duration of ownership of real estate of the persons entered for the first time.

© Scientific Library of Tver State University

Latest publications:

Why are we selling our house? The reasons can be very different: moving to another city, country, village, or changing jobs and others. The decision was made finally and irrevocably

History of the estate...is it important?

Perhaps someone was lucky enough to live in some old estate, the owner of which was previously an aristocrat. In such a house you can feel yourself in his shoes, try to understand what he thought about and how he lived

Parameters of high-rise buildings - an important aspect of construction

High-rise buildings have become characteristic contours of the modern urban landscape of many cities. The construction of such buildings not only makes the city modern, but also provides carefree living for a large number of people on a small plot of land.

How to save for an apartment?

More than once, and I am sure that everyone asked the question, where to get money to buy real estate? How to accumulate them as quickly as possible? After all, buying an apartment in large cities is not a cheap pleasure, and even an additional payment for exchange or a down payment on a mortgage is a very large amount.

If you want to have the last word, write a will.

The practice of writing wills is widely developed among the population of Europe and America, but in our country - somehow not so much. In fact, a will is about caring for your loved ones.

The first group of crafts (leatherworking, furriery, shoemaking) is caused by the need to process the large number of animal skins received every year.

There were two types of artisan tanners. Some sold the tanned leather to shoemakers, others processed the skins for a fee - 1-2 rubles per piece (mid-19th century).

Many peasants near Krasny Kholm and in a number of villages in Vesyegonsky district, for example, in the village of Telyatovo, were engaged in this craft. At the Moscow exhibition of 1876, cowhide leather made by a peasant from the village of Kosyakovo, Vesyegonsky district, was exhibited, selling for 6 rubles. 50 kopecks, raw bull skin for saddlers, made by peasant Yakov Rokofiev from the village of Nikonikha. Residents of the village were engaged in shoemaking. Golovkovo, Toloshmanka, Kozly, but in general it was not widespread.

The second group of peasant crafts was associated with the forest. Up to a million forest roots were harvested annually. Carpenters, joiners, wood sawing and shingle preparation craftsmen, coopers, and wheelwrights worked in the district.

Peasants made carts, sleighs, and baskets in large quantities. Pine and spruce buckets and tubs were especially valued for the beauty of their finish and convenience. The Putilov volost was famous for this. Coopers lived in the village of Voronovo, wheelwrights - in the village of Lyuber, basket makers - in the village of Strelitsa.

Resin occupied an important place in forestry. Spruce resin was used to produce pitch and rosin, pine resin was used to produce turpentine and tar. Turpentine was distilled from stumps, twigs and dead wood, which were primarily extracted from swampy areas. Then they dug up stumps and collected dead wood from the forests. In winter, peasants mined turpentine. We got it in the simplest way. The wood was crushed into thin chips, placed in cast-iron cauldrons embedded in stoves, and, maintaining the fire, the turpentine was distilled out in the same way as alcohol.

Tar was prepared by distilling resin from burnt wood, for which they used mainly pine stumps, and old stumps were preferred to fresh ones, as they were the most saturated with resin. Pine tar was used to lubricate wooden products and wheels, and that obtained from birch bark was used for tanning leather and making yuft.

By 1871, in the Zamolozhsky region of Vesyegonsky district, many peasant families became greatly impoverished. The provincial government decided to help them and for this purpose sent its employee K.E. to the district. Fin-gstena. He found that in dd. Vasyutino, Guzeevo, Sutoki, Martemyenovo peasants have long been engaged in tar smoking, but all their factories were very antediluvian and looked like huts 2.5 x 2.5 fathoms and a fathom high. Peasants bought pine stumps at high prices at state-owned dachas, and sold the resin to traders for next to nothing.

K.A. Fingsten brought four agreements on the formation of artels - Vasyutinskaya, Zabolotskaya, Spirovskaya and Sundukovskaya - which were allocated loans by the zemstvo for 6-10 years. In addition, the Vesyegonsky zemstvo petitioned the ministry so that the sale of tar material would be carried out not by stumps and fathoms, as was previously practiced, but by dachas or quarters with payment not in advance, but after distillation of the raw materials. In this situation, the peasants could dig and transport stumps whenever it was convenient for them.

The ministry agreed with the payment procedure and sent it to the Smolnik administration. In turn, a resident of those places, Prince S.A. Putyatin proposed protecting peasants from local profiteers by building artel warehouses. The provincial government allocated funds for their construction.

All this has borne fruit. During the 1872 season, the artels produced 3,272 pounds of resin and sold it twice as expensive as before - 60 kopecks. per pood.

Looking at this, the Dobrovsky, Topalkovsky, Lukinsky and Garodovsky peasants wanted to organize their own artels.

The peasants valued the attention of the zemstvo very much, carefully repaid the loan and provided a lot of good products. The zemstvo's assistance to the poorest population achieved its goal. Over the past year, the peasants of the Zamolozhsky region have noticeably improved their financial situation.

To support the tannery and furrier crafts in Vesyegonsky district, willow bark was widely harvested, which was done in peasant families from young to old. Bark was sold for 10-12 kopecks per pood.

Some peasants, in the months free from agricultural work, burned coal for blacksmithing (there were 116 forges in the district). For this purpose, they dug a hole 3x3 m and a meter deep and laid freshly sawn and unused logs in intersecting rows. The stack was set on fire and covered with earth. The wood was smoldering, and it was only necessary to make sure that no fire broke through, otherwise ash could form instead of coal. The coal was strong and gave a lot of heat. By the way, I very often came across such pits for producing coal (of course, former ones) in our forests.

Many peasants supported their financial situation by hunting. There were a lot of animals. According to the zemstvo, about a hundred bears were killed annually in Vesyegonsky district. Mostly they went after the bear with a spear. Marten hunting was considered a more delicate matter, and few people practiced it. Most of all, hunters hunted foxes, hares and squirrels, but they also hunted badgers, polecats, weasels, raccoons, and wolves.

In the middle of the 19th century, forests and reservoirs were literally teeming with game birds: wood grouse, hazel grouse, partridges, ducks, snipe (this widespread trade was, for example, in the village of Sazhikha).

A large amount of mushrooms were harvested in the forests of Vesyegonsky district. 30 thousand poods of them were exported from the province for sale. As now, many Veseyegon residents harvested large quantities of wild berries: cranberries, lingonberries, blueberries, cloudberries, raspberries.

The abundance of rivers and their full flow made it possible to engage in fishing. Fish was caught in all possible ways: nets, seines, dragnets, nets, tops, nets, fishing rods, spears.

In the 1880s, a pound of frozen fish cost 1.5 rubles, and five-bucket barrels of salted perch cost 2 rubles. 80 kop. They caught a lot of crayfish for the taverns.

In places where red clay occurs (villages Kishkino, Pashkovo, Popadino, Aksenikha, Levkovo, Egna, etc.), brick production and pottery developed. For example, a brick factory in the village of Koshcheevo produced 9 thousand pieces of red brick per year. In total, there were 8 brick factories in the district.

They were very active in the wool-beating and felting crafts in the district. Only in dd. In Gorchakovo, Valyovo, Badkovo, Borikhino the boots of 30 peasants were lying around. Felted boots made by peasants then cost from 2 rubles. 40 kopecks up to 5 rub. 50 kopecks Sherstobits lived in dd. Sbryndino, Troitskoye, Alexandrov, Lukino, Voronovo, Makarino and others.

Weaving and knitting stockings and mittens was a women's craft.

Blacksmithing has been known in Vesyegonsky district since ancient times. In the 19th century, there was one forge for every 70 households. In total there were 116 forges. They mainly specialized in the production of nails and made them from the size of a crutch to a small shoe pin. In addition, they forged scythes, axes, sickles, and were engaged in the production of ploughshares, spades, knives, and gratings for temples. Blacksmithing was widespread in Uloma and in the areas of the present Vologda region, in its. Kesma, Lekma, dd. Peremut, Staroe Nikulino, Dubrava, etc.

Handicraft specialties and latrine trades were very common in Vesyegonsky district. In the middle of the 19th century there were 39 of them: peasants from the village of Ablazino - farm laborers in Rybinsk district; the village of Abrosimovo - ship workers on the Volga; village Alferove - carpenters, carriers of goods; village of Are-fino - firewood merchants; village of Bolshoye Myakishevo - carpenters, boat builders; village of Bolshoye Ovsyanikovo - making planks, laboring; village of Bolshoye Fominskoye - cab drivers, sex workers in St. Petersburg; d. Volnitsy-no - carriage, day laborers; dd. Eremeytsevo, Vybor, Gorbachev - procurement and sale of firewood; village of Grigorovo - transportation, trade in firewood; village of Dor - forest drivers, farm laborers, bridge workers; village Ilyinskoye - ship workers on the Volga, wheelwrights; With. Kesma - blacksmithing, carpentry; Konik village, Kosodavl village - farm laborers, carriers of nails from Uloma to Moscow and Tver; village of Kuzminskoye - carpenters, farm laborers, shepherds in the Yaroslavl province; village of Lopatikha - growing garden seeds, making brushes, carpenters, carters of firewood; d. Loshitsy - dray drivers; village Makarino - bridge workers in St. Petersburg; the village of Medvedkovo - carriers of nails and groceries; village Moseevskoye - forest sawyers; Ozerki village

Fishermen, blacksmiths (nailers); village Ogibalovo - potters; With. Chernetskoe

Janitors, stall traders, coopers.

I have listed only some of the crafts. It should be noted that the vast majority of craftsmen were engaged in labor in the Yaroslavl province, collecting firewood and transporting it; many were nail carriers from Uloma, shipworkers on the Volga, carpenters, roofers, joiners, floor workers, and paving workers.

Residents of the Topalkovsky volost were engaged in the extraction of limestone used for the construction of churches, houses, and the production of lime and millstones. Here, on the banks of the Mologa, there were quite extensive deposits of limestone. By the way, above the village of Kreshnevo along the Kesma River there were deposits of this stone. Local residents don’t even know about it now.

In passing, I note that in the Vesyegonsky district in the 1890s there were 121 water mills and about 60 windmills. On Reya alone there were 12 water mills, on Kesma - 10. By the way, small mills, incl. and steam houses located outside urban villages were not taxed.

The government strongly encouraged the development of crafts and trades. The regulation on duties for the right of trade and crafts allowed “rural inhabitants of any rank to sell supplies of all kinds and rural products, as well as peasant products, without paying duties at bazaars, markets and marinas, in cities and villages, from carts, ships, boats and chests” .

Agricultural establishments, such as oil mills, sawmills, brick factories, etc., maintained outside urban settlements for processing materials from their own or local agriculture, if they had no more than 16 employees and did not use machines and projectiles driven by steam or water, were exempt from paying duties.

As we see, the peasants had a certain, sometimes not only good help, but also a source of comfortable existence due to crafts and trades. Thus, the most expensive peasant work - spring and autumn plowing - was paid per day within 1 ruble, and the cheapest - 30 kopecks. From April 1 to November 1 (excluding holidays), peasants could have about 180 working days. Roughly estimating that one half of them was paid at the highest rate, the other at the lowest rate, we find that earnings from peasant labor itself amounted to 117 rubles.

The same sums in the 1880s were provided by the potting, blacksmithing, carriage, fishing, shoemaking, leather industries, as well as bark harvesting.

Two-thirds of agricultural earnings came from felting, cooperage, wheelwrighting, and tailoring; all the rest made up half of the indicated amount.

To have an idea of the purchasing power of the peasant of that time, I give some prices: a spruce hut cost 52-70 rubles; pine - 63-105 rubles; barge - 210 rubles, semi-barque - 70 rubles; team and harness - 6 rubles, cow - 20-30 rubles, sheep - up to 5 rubles. A bucket of cottage cheese cost 60 kopecks, milk - up to 30 kopecks. Taxes and quitrents for one adult and one minor were 26 rubles per year. 21 kopecks

Dairy farming occupied an important place in agriculture. There were rich meadows on the flooded lands of Mologa. At the beginning of the 20th century, Vesyegonsky district produced at least 200 thousand pounds of oil per year, which was sold even abroad. Five large and many small cheese factories produced hundreds of pounds of cheese.

Various crafts and trades were not only organically combined with agricultural production, but also provided constant work throughout the year, improved the well-being of peasant families, instilled hard work in their children and maintained high morality in the villages (a view from today). Of course, this was a good experience in organizing work and life, but I am far from idealizing the social situation of the peasantry in the 19th century.

Firstly, not all peasant families were active and energetic. As now, so then there were quitters and lazybones, idiots, thieves, criminals, hooligans and boors, rapists. It mattered a lot who the peasants were before the reform of 1861 - state, landowner, appanage. Of course, the landowners were different, but serfdom left its mark on the psychology of the peasant. If in our time political and economic freedoms have released agriculture with all its vices and problems, adding new ones, then in the 19th century peasant communities and the church actively prevented this.

Anatoly Ananyev wrote: “In past centuries, the face of the city, palaces, temples, and symbols of power have changed more than once. But... the life and work of the commoner farmer remained unchanged.” Meanwhile, history testifies that peoples and states are destroyed and perish not from physical violence or economic oppression, but only when the roots of morality are cut off and spiritual emptiness sets in.

Secondly, one cannot assess the situation of the peasantry abstractly, in isolation from reality. Until the 1840s, peasants built themselves black huts; there were no chimneys in the stoves. When such a hut was heated, the whole family, including the elderly and children, had to go outside. But even after the State Property Administration banned such buildings for state peasants, landowners and peasants continued to build them, valuing black huts for their dryness, hygiene and durability.

About a sixth of the hut was occupied by the stove. There were wide benches along the perimeter walls, with shelves nailed above them, where people coming from the street would put hats, mittens, and various materials for crafts and homework. In the front corner, opposite the stove, there was always a model where the icons stood. Below it was a long table with large drawers for storing spoons, knives and leftover pieces from dinner.

The peasants' food consisted mainly of bread, vegetables, milk, mushrooms and berries. For the first course they served cabbage soup. They were most often cooked from sour gray cabbage, seasoned with a handful of oatmeal or barley. During Lent they prepared cabbage soup, flavored it with finely chopped onions, put one spoonful of sour cream in the meat eater, and also ate it with fresh garlic or horseradish.

Most families ate meat only on holidays. Of the fats in the diet, hemp or flaxseed oil predominated, which, to save money, was put in the former (usually in stews). Potato soup was made from boiled and mashed potatoes and, like cabbage soup, was seasoned with cereals, onions, vegetable oil, and sour cream. For the first course we cooked a mush-like soup.

Scrambled eggs were made from a bowl of milk into which one egg was broken. This was considered a necessary food for life - easy and nutritious.

Milk - fresh and sour - was eaten with the addition of cottage cheese. Pies were often baked with rye, less often with barley, and they were filled with onions, fish, porridge or cottage cheese. Pancakes baked from oatmeal, barley or buckwheat flour were eaten with vegetable oil, lard, sour cream, milk and rarely with cow's butter. Original flatbreads were prepared from rye or barley flour with crushed hemp seeds or cottage cheese. The Karelians baked a special kind of flatbread - kunkushki. Liquidly crushed peas or liquid oatmeal were poured onto thinly rolled unleavened dough and steamed in oil. The Russians filled these flatbreads with cottage cheese, folded them in half and called them sochny. During Lent they ate kulaga made from rye malt, fermenting it with lingonberries or viburnum.

In Vesyegonsky district they loved oatmeal jelly.

Potatoes were cooked in a frying pan with meat or in a tray with milk and eggs. For breakfast they usually ate boiled potatoes with salt and bread.

The peasants tried to prepare as many mushrooms as possible and often consumed them: salted with onions, butter or sour cream; salted, fried with the same seasoning; fresh baked mushrooms with salt, fresh fried; boiled in water with onions, a spoonful of cereal and butter or sour cream; dried boiled, dried boiled with cold kvass and horseradish.

During Lent they ate turyu made from crumbled rye bread with kvass, onions, salt, and vegetable oil. Cold dishes were dominated by grated radish with kvass, sliced, with hemp or vegetable oil.

A peasant's lunch usually consisted of cabbage soup, potatoes and something to go with it. Wealthy peasants could afford cold food, cabbage soup, potatoes and porridge, and pies every Sunday. They also had meat in their cabbage soup on weekdays.

During frequent crop failures, peasants had to eat bread made from straw or quinoa, moss, roots, and tree bark.

They lit the hut with torches. They were chopped up to two arshins (142 cm) long, dried and inserted into the light. Children usually did this. At this time, adults were spinning flax, sewing, weaving bast shoes, and taking up their craft. Under the burning splinters there was a large trough.

But in the 20th century, the shocks of revolution, civil war, and then collectivization largely destroyed this potential.

And yet I.A. Ilyin consoles the Russian people: “And no matter how difficult it is in life and how hard it is in your soul, believe in you, who selflessly love Russia: the just cause will win. And therefore, never be embarrassed by the dominance of evil, it is temporary and transitory, but seek first of all and most of all rightness: only it is truly vital and only in it will a new force be born and from it will arise, leading, saving and guiding.”