When did the Russian Truth Code appear? Russian truth - basic economic principles. Headhunting, flow and plunder

Read also

“Russian Truth” is a legal document of Ancient Rus', a collection of all laws and legal norms that existed in the 10th-11th centuries.

“Russian Truth” is the first legal document in Ancient Rus', which united all the old legal acts, princely decrees, laws and other administrative documents issued by different authorities. “Russian Truth” is not only an important part of the history of law in Russia, but also an important cultural monument, since it reflects the way of life of Ancient Rus', its traditions, principles of economic management, and is also an important source of information about the written culture of the state, which that moment was just emerging.

The document includes rules of inheritance, trade, criminal law, as well as principles of procedural law. “Russian Truth” was at that time the main written source of information about social, legal and economic relations on the territory of Rus'.

The origin of “Russian Truth” today raises quite a few questions among scientists. The creation of this document is associated primarily with the name - the prince collected all the legal documents and decrees that existed in Rus' and issued a new document around 1016-1054. Unfortunately, not a single copy of the original “Russian Pravda” has survived, only later censuses, so it is difficult to say exactly about the author and the date of creation of “Russian Pravda”. “Russian Truth” was rewritten several times by other princes, who made modifications to it according to the realities of the time.

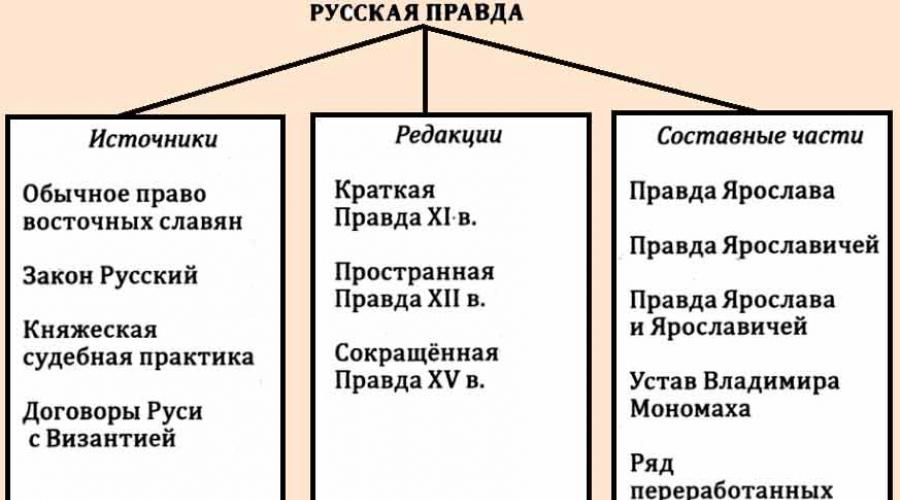

Main sources of "Russian Truth"

The document exists in two editions: short and lengthy (more complete). The short version of “Russian Truth” includes the following sources:

- Pokon virny - determining the order of feeding the prince's servants, vira collectors (created in the 1020s or 1030s);

- Pravda Yaroslav (created in 1016 or in the 1030s);

- Pravda Yaroslavich (does not have an exact date);

- A lesson for bridge workers - regulation of wages for builders, pavement workers, or, according to some versions, bridge builders (created in the 1020s or 1030s).

The short edition contained 43 articles and described new state traditions that appeared shortly before the creation of the document, as well as a number of older legal norms and customs (in particular, the rules of blood feud). The second part contained information about fines, violations, etc. The legal foundations in both parts were built on a principle quite common for that time - class. This meant that the severity of the crime, the punishment or the size of the fine depended not so much on the crime itself, but on what class the person who committed it belonged to. In addition, different categories of citizens had different rights.

A later version of “Russian Truth” was supplemented by the charter of Yaroslav Vladimirovich and Vladimir Monomakh, the number of articles in it was 121. “Russkaya Pravda” in an expanded edition was used in court, civil and ecclesiastical, to determine punishment and settle commodity-money litigation and relations in general .

In general, the norms of criminal law described in Russian Pravda correspond to the norms adopted in many early state societies of that period. The death penalty is still retained, but the typology of crimes is significantly expanding: murder is now divided into intentional and unintentional, different degrees of damage are designated, from intentional to unintentional, fines are levied not at a single rate, but depending on the severity of the offense. It is worth noting that “Russkaya Pravda” describes fines in several currencies at once for the convenience of the legal process in different territories.

The document also contained a lot of information about the legal process. “Russian Truth” determined the basic principles and norms of procedural legislation: where and how it is necessary to hold court hearings, how it is necessary to contain criminals during and before the trial, how to judge them and how to carry out the sentence. In this process, the class principle mentioned above is preserved, which implies that more noble citizens could count on a more lenient punishment and more comfortable conditions of detention. “Russian Truth” also provided for a procedure for collecting monetary debt from a debtor; prototypes of bailiffs appeared who dealt with similar issues.

Another side described in “Russkaya Pravda” is social. The document defined different categories of citizens and their social status. Thus, all citizens of the state were divided into several categories: noble people and privileged servants, which included princes, warriors, then ordinary free citizens, that is, those who were not dependent on the feudal lord (all residents of Novgorod were included here), and the lowest category were considered dependent people - peasants, serfs, serfs and many others who were in the power of feudal lords or the prince.

The meaning of "Russian Truth"

“Russian Truth” is one of the most important sources of information about the life of Ancient Rus' at the earliest period of its development. The presented legislative norms allow us to get a fairly complete picture of the traditions and way of life of all segments of the population of the Russian land. In addition, “Russian Truth” became one of the very first legal documents that was used as the main national legal code.

The creation of the “Russian Pravda” laid the foundations for the future legal system, and when creating new codes of law in the future (in particular, the creation of the Code of Laws of 1497), it always remained the main source, which was taken as a basis by legislators not only as a document containing all acts and laws, but also as an example of a single legal document. “Russian Truth” for the first time officially consolidated class relations in Rus'.

INTRODUCTION

The largest monument of Old Russian law and the main legal document of the Old Russian state was a collection of legal norms, called Russian Truth, which retained its significance in later periods of history. Its norms underlie the Pskov and

Novgorod judgment letters and subsequent legislative acts of not only Russian, but also Lithuanian law. More than a hundred lists of Russian Truth have survived to this day. Unfortunately, the original text of Russian Truth has not reached us. The first text was discovered and prepared for publication by the famous Russian historian V.N. Tatishchev in

1738. The name of the monument differs from European traditions, where similar collections of law received purely legal titles - law, lawyer. In Rus' at that time the concepts were known

“charter”, “law”, “custom”, but the document is designated by the legal-moral term “Truth”. It represents a whole complex of legal documents of the 11th - 12th centuries, the components of which were the Most Ancient Truth (circa 1015), Truth

Yaroslavich (about 1072), Charter of Monomakh (about 1120-1130)

.Russian Truth, depending on the edition, is divided into Brief,

Extensive and Abbreviated.

The Brief Truth is the oldest edition of the Russian Truth, which consisted of two parts. Its first part was adopted in the 30s. XI century . The place of publication of this part of the Russian Pravda is controversial, the chronicle points to Novgorod, but many authors admit that it was created in the center of the Russian land - Kyiv and associate it with the name of Prince Yaroslav the Wise (Pravda Yaroslav). It included 18 articles (1-18) and was entirely devoted to criminal law. Most likely, it arose during the struggle for the throne between Yaroslav and his brother Svyatopolk (1015 - 1019).

. Yaroslav's hired Varangian squad came into conflict with the Novgorodians, which was accompanied by murders and beatings. In an effort to resolve the situation, Yaroslav appeased the Novgorodians by “giving them the Truth and writing off the charter, thus telling them: walk according to its charter.” Behind these words in the 1st Novgorod Chronicle is the text of the Most Ancient Truth.

The characteristic features of the first part of the Russian Truth are the following: the action of the custom of blood feud, the lack of a clear differentiation of the size of fines depending on the social affiliation of the victim. The second part was adopted in Kyiv at the congress of princes and major feudal lords after the suppression of the uprising of the lower classes in 1086 and received the name Pravda

Yaroslavich. It consisted of 25 articles (19-43), but in some sources articles 42-43 are separate parts and are called accordingly: Pokonvirny and Lesson of Bridge Workers. Its title indicates that the collection was developed by three sons

Yaroslav the Wise with the participation of major persons from the feudal environment. There are clarifications in the texts, from which we can conclude that the collection was approved no earlier than the year of Yaroslav’s death (1054) and no later than 1077 (the year of the death of one of his sons)

The second part of the Russian Truth reflects the process of development of feudal relations: the abolition of blood feud, the protection of the life and property of feudal lords with increased penalties. Most of the articles

The Brief Truth contains norms of criminal law and judicial process

.

The Extensive Truth was compiled after the suppression of the uprising in Kyiv in 1113. It consisted of two parts - the Court of Yaroslav and the Charter of Vladimir Monomakh. Long edition of the Russian

Pravda contains 121 articles.

Extensive Truth is a more developed code of feudal law, which enshrined the privileges of feudal lords, the dependent position of smerds, purchases, and the lack of rights of serfs. Extensive Truth testified to the process of further development of feudal land ownership, paying much attention to the protection of ownership of land and other property. Certain norms of the Extensive Truth determined the procedure for transferring property by inheritance and concluding contracts.

Most of the articles relate to criminal law and judicial process.

The Abridged Truth was formed in the middle of the 15th century. from recycled

Dimensional Truth.

It is indisputable that, like any other legal act, Russian

Truth could not arise out of nowhere, without a basis in the form of sources of law. All that remains for me is to list and analyze these sources, to evaluate their contribution to the creation of the Russian

Truth. I would like to add that the study of the legal process is not only purely cognitive, academic, but also political and practical in nature. It allows a deeper understanding of the social nature of law, features and traits, and makes it possible to analyze the causes and conditions of its emergence and development.

1.1. SOURCES OF ANCIENT RUSSIAN LAW

The most ancient source of any law, including Russian, is custom, that is, a rule that was followed due to repeated application and became a habit of people. There were no antagonisms in the clan society, therefore customs were observed voluntarily. There were no special bodies to protect customs from violation. Customs changed very slowly, which was quite consistent with the pace of change in society itself. Initially, the law developed as a set of new customs, the observance of which was obligated by the nascent state bodies, and primarily by the courts.

Later, legal norms (rules of behavior) were established by acts of princes. When a custom is sanctioned by government authority, it becomes a rule of customary law.

In the 9th – 10th centuries in Rus' it was precisely the system of norms of oral

, common law. Some of these norms, unfortunately, were not recorded in the collections of law and chronicles that have reached us. one can only guess about them from individual fragments in literary monuments and treaties between Rus' and Byzantium in the 10th century.

One of the most famous ancient Russian legal monuments of that time, in which these norms were reflected, as I already mentioned in the introduction, is the largest source of ancient Russian law - Russian Truth. The sources of its codification were the norms of customary law and princely judicial practice. The norms of customary law recorded in the Russian Pravda include, first of all, the provisions on blood feud (Article 1 of the Communist Code) and mutual responsibility. (Art.

20 CP). The legislator shows a different attitude towards these customs: he seeks to limit blood feud (narrowing the circle of avengers) or completely abolish it, replacing it with a fine - vira (there is a similarity with the “Salic truth” of the Franks, where blood feud was also replaced with a fine); in contrast to blood feud, mutual responsibility is preserved as a measure that binds all members of the community with responsibility for their member who committed a crime (“Wild Virus” was imposed on the entire community)

In our literature on the history of Russian law, there is no consensus on the origin of Russian Pravda. Some consider it not an official document, not a genuine monument of legislation, but a private legal collection compiled by some ancient Russian lawyer or group of lawyers for their own personal purposes.. Others believe

Russian Pravda is an official document, a genuine work of the Russian legislative power, only spoiled by copyists, as a result of which many different lists of Pravda appeared, which differ in the number, order and even text of articles.

One of the sources of Russian Truth was the Russian Law

(rules of criminal, inheritance, family, procedural law). Disputes about its essence still continue to this day. In history

Russian law does not have a consensus on this document. According to some historians, supporters of the Norman theory of origin

The Old Russian state, the Russian Law was Scandinavian law, and the famous Russian historian V.O. Klyuchevsky believed that the Russian Law was a “legal custom”, and as a source of Russian Pravda it is not “the primitive legal custom of the Eastern Slavs, but the law of urban Rus', formed from quite diverse elements in 9-

11th centuries." According to other historians, the Russian Law was customary law created in Rus' over the centuries and reflected relations of social inequality and was the law of an early feudal society, located at a lower stage of feudalization than the one at which the Most Ancient Truth arose. Russian Law was necessary for the conduct of princely policies in the annexed Slavic and non-Slavic lands. It represented a qualitatively new stage in the development of Russian oral law in the conditions of the existence of the state. It is known that it is also partially reflected in the treaties between Rus' and the Greeks.

Treaties with the Greeks are a source of exceptional importance that allowed the researcher to penetrate the secrets of Rus' in the 9th – 10th centuries. These treaties are the clearest indicator of the high international position of the Old Russian state; they are the first documents of the history of Rus' in the Middle Ages. Their very appearance speaks of the seriousness of relations between the two states, of class society, and the details quite clearly introduce us to the nature of the direct relations between Rus' and Byzantium. This is explained by this. that in Rus' there was already a powerful class interested in concluding treaties. They were needed not by the peasant masses, but by princes, boyars and merchants. We have four of them: 907, 911, 944, 972. They pay a lot of attention to the regulation of trade relations, the definition of the rights that Russian merchants enjoyed in

Byzantium, as well as the norms of criminal law. From the agreements with the Greeks, we have private property, which its owner has the right to dispose of and, among other things, transfer it by will.

According to the peace treaty of 907, the Byzantines agreed to pay

Rus' a monetary indemnity, and then pay a monthly tribute, provide a certain food allowance for Russian ambassadors and merchants coming to Byzantium, as well as for representatives of other states. Prince Oleg achieved duty-free trading rights in Byzantine markets for Russian merchants. The Russians even received the right to wash in the baths of Constantinople, before which only free subjects of Byzantium could visit them. The agreement was sealed during Oleg’s personal meeting with the Byzantine Emperor Leo VI. As a sign of the end of hostilities, the conclusion of peace,

Oleg hung his shield on the gates of the city. This was the custom of many peoples of Eastern Europe. This treaty presents us with Russians no longer as wild Varangians, but as people who know the sanctity of honor and national solemn conditions, have their own laws establishing personal security, property, the right of inheritance, the power of wills, and have internal and external trade.

In 911, Oleg confirmed his peace treaty with Byzantium. In the course of lengthy ambassadorial treaties, the first detailed written agreement in the history of Eastern Europe was concluded between Byzantium and

Russia. This agreement opened with an ambiguous phrase: “We are from the Russian family... sent from Oleg the Grand Duke of Russia and from everyone who is at his hand - the bright and great princes and his great boyars...”

The treaty confirmed “peace and love” between the two states. IN

In 13 articles, the parties agreed on all economic, political, and legal issues of interest to them, and determined the responsibility of their subjects if they committed any crimes. One of the articles talked about concluding a military alliance between them. From now on, Russian troops regularly appeared as part of the Byzantine army during its campaigns against enemies. It should be noted that among the names of the 14 nobles used by the Grand Duke to conclude peace terms with the Greeks, there is not a single Slavic one. Having read this text, you might think that only the Varangians surrounded our first sovereigns and used their power of attorney, participating in the affairs of government.

The 944 treaty mentions all Russian people in order to more strongly emphasize the idea immediately following this phrase about the binding nature of treaties for all Russian people. Treaties were concluded not on behalf of the veche, but on behalf of the prince and the boyars. Now we can have no doubt that all these noble and powerful men were large landowners, not just yesterday, but with a long history of their own, who managed to grow stronger in their estates. This is evidenced by the fact that with the death of the head of the family, his wife became the head of such a noble house. Russian Truth confirms this position: “What a husband has laid on a nude, there is also a mistress” (Trinity List, art. 93). A significant part of the norms of customary oral law in a processed form entered the Russian

The truth. For example, Article 4 of the 944 treaty is generally absent from the 911 treaty, which establishes a reward for the return of a runaway servant, but a similar provision is included in the Longitudinal

Truth (Article 113). Analyzing Russian-Byzantine treaties, it is not difficult to come to the conclusion that there can be no talk of any dominance of Byzantine law. They either give the so-called contractual, on the basis of a compromise between Russian and Byzantine law (a typical example is the rule on murder) or implement the principles of Russian law - Russian law, as we see in the rule on blows with a sword “Whether to strike with a sword or to hit with a sword or a vessel, for that emphasis or beating and give a liter

5 silver according to the Russian law” or in the norm on theft of property.

They indicate a fairly high development of inheritance law in Rus'.

But I think Russia’s adoption of Christianity had a special influence on the development of the law of ancient Rus'. In 988, during the reign of

In Kyiv, Prince Vladimir, the so-called “Baptism of Rus'” takes place. The process of Rus''s transition to the new faith proceeds gradually, encountering certain difficulties associated with the change in the old, established worldview and the reluctance of part of the population to convert to the new faith.

At the end of the 10th - beginning of the 11th century, along with the new religion, new legislative acts came to pagan Rus', mainly Byzantine and South Slavic, containing the fundamental foundations of church - Byzantine law, which later became one of the sources of the legal monument I was studying. In the process of strengthening the position of Christianity and its spread on the territory of Kievan Rus, a number of Byzantine legal documents - nomocanons, i.e. associations of canonical collections of church rules of the Christian church and decrees of the Roman and Byzantine emperors on the church.

The most famous of them are: a) The Nomocanon of John Scholasticus, written in the 6th century and containing the most important church rules, divided into 50 titles, and a collection of secular laws of 87 chapters; b) Nomocanon 14 titles; c) Eclogue, published in 741 by the Byzantine Emperor Leo

Iosovryanin and his son Konstantin, dedicated to civil law (16 titles out of 18) and regulating mainly feudal land ownership; d) Prochiron, published at the end of the 8th century by Emperor Constantine, called in Rus' the City Law or the Manual Book of Laws; e) The Law of Judgment for People, created by the Bulgarian Tsar Simeon.

Over time, these church-legal documents, called in Rus'

The Helmsmen's Books take on the force of full-fledged legislative acts, and soon after their dissemination the institution of church courts, existing along with princely ones, begins to take root. Now we should describe in more detail the functions of church courts. Since the adoption of Christianity, the Russian Church has been granted dual jurisdiction. Firstly, she judged all Christians, both clergy and laity, on certain matters of a spiritual and moral nature. Such a trial was to be carried out on the basis of the nomocanon brought from Byzantium and on the basis of church statutes issued by the first Christian princes of Rus' Vladimir Svyatoslavovich and Yaroslav

Vladimirovich. The second function of church courts was the right to trial Christians (clergy and laity) in all matters: church and non-church, civil and criminal. Church court in non-church civil and criminal cases, which extended only to church people, was to be carried out according to local law and caused the need for a written set of local laws, which was the Russian Truth.

I would highlight two reasons for the need to create such a set of laws:

1) The first church judges in Rus' were Greeks and southern Slavs, not familiar with Russian legal customs, 2) Russian legal customs contained many norms of pagan customary law, which often did not correspond to the new Christian morality, so church courts sought, if not completely eliminated, then at least try to soften some of the customs that were most distasteful to the moral and legal sense of Christian judges brought up on Byzantine law. It was these reasons that prompted the legislator to create the document I was studying.

I believe that the creation of a written code of laws is directly related to the adoption of Christianity and the introduction of the institution of church courts. After all, earlier, until the middle of the 11th century, the princely judge did not need a written code of laws, because The ancient legal customs that guided the prince and princely judges in judicial practice were still strong. The adversarial process also dominated, in which the litigants actually led the process. And, finally, the prince, possessing legislative power, could, if necessary, fill in legal gaps or resolve the casual perplexity of the judge.

Also, to make the assertion that the creation of

Russian Pravda was influenced by monuments of church-Byzantine law; the following examples can be given:

1) Russian Truth is silent about the judicial duels that undoubtedly took place in Russian legal proceedings of the 11th - 12th centuries, which were established in the “Russian Law” I mentioned earlier. Also, many other phenomena that took place, but were contrary to the Church, or actions that fell under the jurisdiction of church courts, but on the basis of no

Russian Truth, but church laws (for example, insult with words, insult of women and children, etc.).

2) Even by its appearance, Russian Truth indicates its connection with Byzantine legislation. This is a small codex like the Eclogue and

Prochirona (synoptic codex).

In Byzantium, according to the tradition that came from Roman jurisprudence, a special form of codification was diligently processed, which can be called synoptic codification. Its example was given by the Institutes of Justinian, and further examples are the neighbors of Russian Truth in the Book of the Pilot - Eclogue and

Prochiron. These are brief systematic statements of law, rather works of jurisprudence than legislation, not so much codes as textbooks, adapted for the easiest knowledge of laws.

Comparing the Russian Truth with the monuments of Byzantine church law, summing up the above observations, I came to the conclusion that the text

Russian Pravda was formed in the environment not of a princely court, but of a church court, in the environment of church jurisdiction, the goals of which guided the compiler of this legal monument in his work.

Russian Truth is one of the largest legal works of the Middle Ages. By the time of its origin, it is the oldest monument of Slavic law, entirely based on the judicial practice of the Eastern Slavs. Even Procopius of Caesarea in the 6th century noted that among the Slavs and Antes “all life and laws are the same.” Of course, there is no reason to mean Russian Truth here by “legalization,” but it is necessary to recognize the existence of some norms according to which the life of the Antes flowed and which were remembered by experts in customs and preserved by the clan authorities. It is not for nothing that the Russian word “law” passed on to the Pechenegs and was in use among them in the 12th century. It is safe to say that blood feud was well known at that time, although in a reduced form in Russian Pravda. There is no doubt that a tribal community with customs in the process of decomposition, occurring under the influence of the development of the institution of private ownership of land, turned into a neighboring community with a certain range of rights and obligations. This new community was reflected in Russian Pravda. All attempts to prove any influence on Russian Truth on the part of Byzantine, South Slavic, Scandinavian legislation turned out to be completely fruitless. Russian Truth arose entirely on Russian soil and was the result of the development of Russian legal thought of the X-XII centuries.

1. 2. LEGAL STATUS OF THE POPULATION

All feudal societies were strictly stratified, that is, they consisted of classes, the rights and responsibilities of which were clearly defined by law as unequal in relation to each other and to the state. In other words, each class had its own legal status. It would be a great simplification to consider feudal society from the point of view of exploiters and exploited. The class of feudal lords, constituting the fighting force of the princely squads, despite all their material benefits, could lose their lives - the most valuable thing - easier and more likely than the poor class of peasants. The feudal class was formed gradually. It included princes, boyars, squads, local nobility, posadniks, and tiuns. The feudal lords exercised civil administration and were responsible for a professional military organization. They were mutually connected by a system of vassalage, regulating rights and obligations to each other and to the state. To ensure management functions, the population paid tribute and court fines. The material needs of the military organization were provided by land ownership.

Feudal society was religiously static, not prone to dramatic evolution. In an effort to consolidate this static nature, the state preserved relations with the estates in legislation.

The Russian Pravda contains a number of norms that determine the legal status of certain groups of the population. The personality of the prince occupies a special place. He is treated as an individual, which indicates his high position and privileges. But further in its text it is quite difficult to draw a line dividing the legal status of the ruling stratum and the rest of the population. We find only two legal criteria that particularly distinguish these groups in society: norms on increased (double) criminal liability - double penalty (80 hryvnia ) for the murder of a representative of the privileged layer (Article 1 of the PP) of princely servants, grooms, tiuns, firemen. But the code is silent about the boyars and warriors themselves. Probably, the death penalty was applied to them for encroachment. The chronicles repeatedly describe the use of execution during popular unrest. And also rules on a special procedure for inheriting real estate (land) for representatives of this layer

(Article 91 PP). In the feudal stratum, the earliest of all was the abolition of restrictions on female inheritance. Church statutes establish high fines for violence against boyars’ wives and daughters, ranging from 1 to 5 hryvnia silver. Also, a number of articles protect the property of feudal lords

. A fine of 12 hryvnia is established for violating the land boundary; fines are also levied for the destruction of beekeepers, boyar lands, and for the theft of hunting falcons and hawks.

The bulk of the population was divided into free and dependent people; there were also intermediate and transitional categories.

The urban population was divided into a number of social groups: boyars, clergy, merchants. “lower classes” (artisans, small traders, workers, etc.) In science, the question of its legal status has not been adequately resolved due to a lack of sources. It is difficult to determine to what extent the population of Russian cities enjoyed urban liberties similar to those in Europe, which further contributed to the development of capitalism in cities. According to the historian's calculations

M.N. Tikhomirov, in Rus' in the pre-Mongol period there existed before

300 cities. City life was so developed that it allowed

IN. Klyuchevsky came up with the theory of “merchant capitalism” in the Ancient

Rus'. M.L. Tikhomirov believed that in Rus' “the air of the city made a person free,” and many runaway slaves were hiding in the cities.

Free city residents enjoyed the legal protection of the Russian

True, they were subject to all articles on the protection of honor, dignity and life. The merchant class played a special role. It early began to unite into corporations (guilds), called hundreds. Usually the “merchant hundred” operated under some church. "Ivanovo Sto" in Novgorod was one of the first merchant organizations in Europe.

The smerds, the community members, were also a legally and economically independent group (they paid taxes and performed duties only in favor of the state).

In science, there are a number of opinions about smerds; they are considered free peasants, feudal dependents, persons in a slave state, serfs, and even a category similar to petty knighthood. But the main debate is conducted along the lines of: free or dependent (slaves). Many historians, for example S.A. Pokrovsky, consider smerds as commoners, ordinary citizens, everywhere presented as Russian Pravda, a free person unlimited in his legal capacity. So S.V. Yushkov saw in the smerds a special category of the enslaved rural population, and B.D. Grekov believed that there were dependent smerds and free smerds. A.A. Zimin defended the idea of the origin of smerds from slaves.

Two articles of Russian Pravda have an important place in substantiating opinions.

Article 26 of the Brief Truth, which establishes a fine for the murder of slaves, in one reading reads: “And in the stink and in the slave 5 hryvnia” (Academic list) In the Archaeographic list we read: “And in the stink in the serf 5 hryvnia” In the first reading it turns out that in case of murder of a serf and a serf, the same fine is paid. From the second list it follows that Smerd has a slave who is killed

. It is impossible to resolve the situation.

Article 90 of the Extensive Truth states: “If the smerd dies, then the inheritance goes to the prince; if he has daughters, then give them a dowry.” Some researchers interpret it in the sense that after the death of Smerd, his property passed entirely to the prince and he is a man of a “dead hand,” that is, unable to pass on an inheritance. But further articles explain the situation - we are talking only about those smerdas who died without sons, and the exclusion of women from inheritance is characteristic at a certain stage of all the peoples of Europe. From this we see that the smerd ran the household together with his family.

However, the difficulties of determining the status of a smerd do not end there. Smerd, according to other sources, acts as a peasant who owns a house, property, and a horse. For the theft of his horse, the law establishes a fine of 2 hryvnia. For “flour” stink, a fine of 3 hryvnia is established. Russian Pravda nowhere specifically indicates a limitation on the legal capacity of smerds; there are indications that they pay fines (sales) characteristic of free citizens. The law protected the person and property of the smerda. For the committed misdeeds and crimes, as well as for obligations and contracts, he bore personal and property liability; for debts, the smerd was in danger of becoming a feudal-dependent purchase; in the legal process, the smerd acted as a full participant.

Russian Pravda always indicates, if necessary, membership in a specific social group (combatant, serf, etc.) In the mass of articles about free people, it is the free people who are meant; about smerds, it comes only where their status needs to be highlighted.

Tributes, polyudye and other extortions undermined the foundations of the community, and many of its members, in order to pay the tribute in full and somehow survive themselves, were forced to go into debt bondage to their rich neighbors. Debt bondage has become the most important source of creating economically dependent people. They turned into servants and slaves who bent their backs on their masters and had virtually no rights. One of these categories were the rank and file

(from the word “row” - agreement) - those who enter into an agreement on their temporary servile position, and his life was valued at 5 hryvnia.

Being a private employee was not always bad; he could turn out to be a key holder or a manager.. A more complex legal figure is procurement.

The Brief Pravda does not mention procurement, but the Long Pravda contains a special charter on procurement. Zakup - a person who worked on the feudal lord’s farm for a “kupa”, a loan, which could include various valuables: land, livestock, money, etc. This debt had to be worked off, and there were no standards. The scope of work was determined by the lender. Therefore, with the increase in interest on the loan, bondage increased and could continue for a long time. The first legal settlement of debt relations between purchases and creditors was made in the Charter of Vladimir

Monomakh after the procurement uprising in 1113. Maximum interest rates on debt were established. The law protected the person and property of the purchaser, prohibiting the master from punishing and taking away property without cause. If the purchase itself committed an offense, the responsibility was twofold: the master paid a fine for it to the victim, but the purchase itself could be issued by the head, i.e. turned into a complete serf. Its legal status changed dramatically.

For attempting to leave the master without paying, the purchaser was turned into a serf. The purchaser could act as a witness in a trial only in special cases: in minor cases (“in small claims”) or in the absence of other witnesses (“out of necessity”). The purchase was the legal figure who most clearly illustrated the process

“feudalization”, enslavement, enslavement of former free community members.

In Russian Pravda, “role” (arable) procurement, working on someone else’s land, in its legal status did not differ from procurement

"non-role." Both differed from hired workers, in particular in that they received payment for work in advance, and not after completion. Role purchases, working on someone else's land, cultivated it partly for the master, partly for themselves. Non-role purchases provided personal services to the master in his home. In the feudal economy, the labor of slaves was widely used, the ranks of which were replenished by prisoners, as well as by ruined fellow tribesmen. The position of the slaves was extremely difficult - they

“They ate below rye bread and without salt because of their extreme poverty.” Feudal shackles tenaciously held a person in a slave position. Sometimes, completely despairing and giving up on all earthly and heavenly hopes, the slaves tried to break them and raised their hands against the offenders-masters. So, in 1066, reports

Novgorod Chronicle, one of the church fanatics, Bishop Stefan, was strangled by his own slaves. The serf is the most powerless subject of law. His property status is special: everything he owned was the property of the master. His personality as a subject of law was not protected by law. In a lawsuit, a slave cannot act as a party. (plaintiff, defendant, witness). Referring to his testimony in court, a free man had to make a reservation that he was referring to the “words of a serf.” The law regulated various sources of servility of the Russian Truth and provided for the following cases: sale into slavery itself, birth from a slave, marriage to a slave, “key holding”, i.e. entering the service of a master, but without a reservation about maintaining the status of a free person. The most common source of servility, not mentioned however in

Russian Pravda, was captured. But if the slave was a prisoner - “taken from the army,” then his fellow tribesmen could ransom him. The price for a prisoner was high - 10 zlatniks, full-weight gold coins of Russian or Byzantine mintage. Not everyone expected such a ransom to be paid for him. And if the slave came from his own Russian family-tribe, then he waited and wished for the death of his master. The owner could, by his spiritual testament, hoping to atone for earthly sins, set his slaves free. After this, the slave turned into a freedman, that is, set free. Slaves stood at the lowest rung even in those ancient times on the ladder of social relations. The sources of servitude were also: the commission of a crime (punishment such as “flow and plunder” included the extradition of the criminal with his head, turning into a slave), the flight of a purchase from the master, malicious bankruptcy (the merchant loses or squanders other people’s property) Life became more difficult, tributes and quitrents increased. The ruin of the community smerds through unbearable exactions gave rise to another category of dependent outcast people. An outcast is a person expelled from his circle by force of difficult life circumstances, who is bankrupt, who has lost his home, family, and household. The name “outcast” apparently comes from the ancient verb “goit”, which in ancient times was equivalent to the word

"live". The very emergence of a special word to designate such people speaks of a large number of disadvantaged people. Izgoystvo as a social phenomenon became widespread in Ancient Rus', and feudal legislators had to include articles about outcasts in the codes of ancient laws, and the church fathers constantly mentioned them in their sermons

So from all of the above, you can get some idea of the legal status of the main categories of the population in

Rus'.

CONCLUSION

Undoubtedly, Russian Truth is a unique monument of ancient Russian law. Being the first written set of laws, it nevertheless quite fully covers a very wide area of \u200b\u200bthe relations of that time. It represents a set of developed feudal law, which reflected the norms of criminal and civil law and procedure.

Russian Truth is an official act. Its text itself contains references to the princes who adopted or changed the law (Yaroslav

Wise, Yaroslavichi, Vladimir Monomakh).

Russian Truth is a monument of feudal law. It comprehensively defends the interests of the ruling class and openly proclaims the lack of rights of unfree workers - serfs, servants.

Russian Truth in all its editions and lists is a monument of enormous historical significance. For several centuries it served as the main guide in legal proceedings. In one form or another, the Russian Truth became part of or served as one of the sources of later judicial charters: the Pskov judicial charter, the Dvina charter of 1550, even some articles of the Council Code of 1649.

The long use of the Russian Pravda in court cases explains to us the appearance of such types of lengthy editions of the Russian Pravda, which were subject to alterations and additions back in the 14th and 16th centuries.

Russian Truth satisfied the needs of princely courts so well that it was included in legal collections until the 15th century. Lists

Extensive Truth was actively disseminated back in the 15th - 16th centuries. And only in

In 1497, the Code of Law of Ivan III Vasilyevich was published, replacing the Extensive

Truth as the main source of law in the territories united within the centralized Russian state.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.

1. GREKOV B.D. Kievan Rus. Politizdat. 1953.

2. ZIMIN A.A. Slaves in Rus'. M. Science. 1973.

3. ISAEV I. A. History of the state and law of Russia. M. 1999.

4. SVERDLOV M.B. From Russian law to Russian Truth. M. 1988.

5. TIKHOMIROV M.N. A manual for studying Russian Truth. Publishing house

Moscow University. 1953.

6. CHRESTOMATHY on the history of state and law of the USSR. Pre-October period.

Edited by TITOV YU.P. and CHISTYAKOVA I.O. M. 1990.

7. KLYUCHEVSKY V.O. Course of Russian history, part 1.5-ed.M

8. SHCHAPOV Y.N. Princely charters and the church in Ancient Rus' 9-14 centuries.

9. YUSHKOV S.V. Russian Truth: Origin, sources, its meaning. M.

a code of ancient Russian law from the era of the Kievan state and the feudal fragmentation of Rus'. Came down to us in lists of the 13th - 18th centuries. in three editions: Brief, Long, Abridged. The first information about the ancient Russian system of law is contained in the agreements of Russian princes with the Greeks, where the so-called “Russian law” is reported. Apparently, we are talking about some monument of a legislative nature that has not reached us. The most ancient legal monument is “Russian Truth”. It consists of several parts, the oldest part of the monument - “The Ancient Truth”, or “The Truth of Yaroslav”, is a charter issued by Yaroslav the Wise in 1016. It regulated the relations of the princely warriors with the residents of Novgorod and among themselves. In addition to this charter, the “Russian Pravda” includes the so-called “Pravda of the Yaroslavichs” (adopted in 1072) and the “Charter of Vladimir Monomakh” (adopted in 1113). All these monuments form a fairly extensive code regulating the life of a person of that time. It was a class society in which the traditions of the tribal system were still preserved. However, they are already beginning to be replaced by other ideas. Thus, the basic social unit spoken of in “Russian Pravda” is not the gens, but the “world”, i.e. community. In "Russian Truth" for the first time such a widespread custom of clan society as blood feud was abolished. Instead, the dimensions of the vira are determined, i.e. compensation for the murdered person, as well as the punishment imposed on the murderer. The vira was paid by the entire community on whose land the body of the murdered man was found. The highest fine was imposed on the murder of the fireman, the head of the community. It was equal to the cost of 80 oxen or 400 rams. The life of a stinker or serf was valued 16 times less. The most serious crimes were robbery, arson or horse theft. They were subject to punishment in the form of loss of all property, expulsion from the community or imprisonment. With the advent of written laws, Rus' rose one more step in its development. Relations between people began to be regulated by laws, which made them more orderly. This was necessary because, along with the growth of economic wealth, the life of each person became more complicated, and it was necessary to protect the interests of each individual person.

Russian Truth, which was formed on the basis of laws that existed in the 10th century, included norms of legal regulation that arose from customary law, that is, folk traditions and customs.

The content of Russian Pravda indicates a high level of development of economic relations, rich economic ties regulated by law. “The truth,” wrote the historian V.O. Klyuchevsky, “strictly distinguishes the giving of property for storage - a “deposit” from a “loan”, a simple loan, a favor out of friendship, from the giving of money in growth from a certain agreed percentage, a short-term interest-bearing loan from a long-term one. and, finally, a loan - from a trade commission and a contribution to a trading company enterprise from an unspecified profit or dividend. The truth further gives a certain procedure for collecting debts from an insolvent debtor during the liquidation of his affairs, and is able to distinguish between malicious and unfortunate insolvency. What is a trade loan and transactions in. credit - it is well known to Russian Pravda. Guests, foreign or foreign merchants, “sold goods” for native merchants, that is, they sold them on credit to the guest, a fellow countryman who traded with other cities or lands, “kunas for purchase.” ", on a commission for the purchase of goods for him on the side; the capitalist entrusted the merchant with "kunas and guests" for turnover from the profit."

At the same time, as can be seen from reading the economic articles of Russian Pravda, profit and the pursuit of profit are not the goal of ancient Russian society. The main economic idea of Russian Pravda is the desire to ensure fair compensation, remuneration for damage caused in the conditions of self-governing collectives. Truth itself is understood as justice, and its implementation is guaranteed by the community and other self-governing groups.

The main function of Russian Pravda is to provide a fair, from the point of view of folk tradition, solution to problems that have arisen in life, to ensure a balance between communities and the state, to regulate the organization and payment of labor for the performance of public functions (collecting food, building fortifications, roads and bridges).

Russian Truth was of great importance in the further development of Russian law. It formed the basis of many norms of the international treaty of Novgorod and Smolensk (XII-XIII centuries), Novgorod and Pskov charters of judgment, Code of Law 1497, etc.

Great definition

Incomplete definition ↓

A law cannot be a law if there is no strong force behind it.

Mahatma Gandhi

Kievan Rus before the baptism of the country by Prince Vladimir was a pagan country. As in any pagan country, the laws by which the state lived were taken from the customs of the country. Such customs were not written down by anyone and were passed on from generation to generation. After the baptism of Rus', the prerequisites were created for the written recording of the laws of the state. For a long time, no one created such laws, since the situation in the country was extremely difficult. The princes had to constantly fight with external and internal enemies.

Under the reign of Prince Yaroslav, the long-awaited peace came to the country and the first written set of laws appeared, which was called “Yaroslav’s Truth” or “Russian Truth of Yaroslav the Wise.” In this legislative collection, Yaroslav tried to very clearly structure the laws and customs that existed in Kievan Rus at that moment. Total Yaroslav's truth consisted of 35 (thirty-five) chapters, in which civil and criminal law were distinguished.

The first chapter contained measures to combat murder, which was a real problem of that time. The new law stated that any death was punishable by blood feud. Relatives of the murdered person have the right to kill the murderer themselves. If there was no one to take revenge on the killer, then he was charged a fine in favor of the state, which was called Viroy. The Russian truth of Yaroslav the Wise contained a complete list of rules that the killer had to transfer to the state treasury, depending on the family and class of the murdered person. Thus, for the death of a boyar it was necessary to pay tiuna (double vira), which was equal to 80 hryvnia. For the murder of a warrior, farmer, merchant or courtier, they demanded viru, 40 hryvnia. The life of slaves (servants), who did not have any civil rights, was valued much cheaper, at 6 hryvnia. With such fines they tried to save the lives of the subjects of Kievan Rus, of whom there were not so many due to the wars. It should be noted that in those days money was very rare for people and the described virs were able to pay only a few. Therefore, even such a simple measure was enough to stop the wave of murders in the country.

The laws that the Russian Truth of Yaroslav the Wise gave to people were harsh, but this was the only way to restore order in the country. As for murders committed while dirty or in a state of intoxication, and the killer was hiding, a levy was collected from all village residents. If the murderer was detained, then half of the vira was paid by the villagers, and the other half by the murderer himself. This measure was extremely necessary to ensure that people did not commit murders during a quarrel, so that everyone passing by felt responsible for the actions of others.

Special conditions of the law

The Russian truth of Yaroslav the Wise also determined the possibility of changing a person’s status, i.e. how a slave could become free. To do this, he needed to pay his master an amount equal to the income not received by the latter, that is, the income that the master can receive from the work of his slave.

In general, the first written set of laws regulated almost all areas of life at that time. Thus, it described in detail: the responsibility of slaves for the safety of the property of their masters; debentures; order and sequence of inheritance of property, etc. The judge in almost all cases was the prince himself, and the place of trial was the princely square. It was quite difficult to prove innocence, since a special ritual was used for this, during which the accused took a red-hot piece of iron in his hand. Afterwards, his hand was bandaged and three days later the bandages were publicly removed. If there were no burns, innocence is proven.

Russian truth of Yaroslav the Wise - this is the first written set of laws that regulated the life of Kievan Rus. After the death of Yaroslav, his descendants supplemented this document with new articles, thereby forming the Truth of the Yaroslavichs. This document regulated relations within the state for quite a long time, right up to the period of fragmentation of Rus'.

Russian Truth became the first collection of laws in Ancient Rus'. Its first editions appeared during the reign of the Kyiv prince Yaroslav the Wise in the first half of the 11th century. He was the initiator of the creation of Russian Truth. The collection was necessary in order to streamline life in a state where people still judged and resolved disputes according to unwritten traditions. All of them are reflected on the pages of this collection of documents.

A brief description of Russian Truth suggests that it stipulates the order of social, legal and economic relations. In addition, the collection contains norms of several types of legislation (hereditary, criminal, procedural and commercial).

Prerequisites

The main goal that Yaroslav the Wise set for the collection was to determine the legal status of the population according to Russian Truth. The emergence of codified norms was common in all medieval European societies. So, in the Frankish state the “Salic truth” was similar. Even the barbaric northern states and the British Isles appeared with their own judges. The only difference is that in Western Europe these documents were created several centuries earlier (starting from the 6th century). This was due to the fact that Rus' appeared later than the feudal Catholic states. Therefore, the creation of legal norms among the Eastern Slavs occurred several centuries later.

Creation of Russian Truth

The most ancient Truth, or the Truth of Yaroslav, appeared in 1016, when he finally established himself in Kyiv. However, this document was not intended for the southern capital, but for Novgorod, since the prince began his reign there. This edition contains mainly various criminal articles. But it was with this list of 18 articles that the creation of Russian Pravda began.

The second part of the collection appeared a few years later. It was called the Truth of the Yaroslavichs (children of the Grand Duke) and affected the legal relations between the residents of the state. In the 1930s, articles appeared regarding the feeding of virniks. These parts exist in the form of a short edition.

However, the collection was supplemented after the death of Yaroslav. The creation of Russian Pravda continued under his grandson Vladimir Monomakh, who managed to briefly unite the appanage principalities (the era of feudal fragmentation was approaching) and complete his Charter. He entered the lengthy edition of Pravda. The lengthy editorial touched on disputes related to the right to property. This was due to the fact that trade and monetary relations were developing in Rus'.

Existing copies

It is known for certain that no original copies of Russian Truth have survived. Domestic historiography discovered later copies when they were discovered and studied. The earliest copy is considered to be a list placed in the Novgorod first chronicle of the 11th century. This is exactly what it became for researchers.

Later, copies and lists were found dating back to the 15th century. Excerpts from them were used in various Helmsman books. Russian Truth ceased to be relevant with the release of the Code of Laws of Ivan III at the end of the 15th century.

Criminal law

A person’s responsibility for crimes is reflected in detail on the pages that Russkaya Pravda contains. The articles fix the difference between intentional and unintentional crimes. There is also a distinction between light and heavy damage. By this measure it was decided what punishment the criminal would be sentenced to.

At the same time, the Slavs still practice what Russkaya Pravda talks about. The articles state that a person has the right to punish the killer of a father, brother, son, etc. If a relative did not do this, then the state announced a reward of 40 hryvnia for the head of the criminal. These were echoes of the previous system that had existed for centuries. It is important to note that Rus' had already been baptized, but remnants of the pagan bloodthirsty era still existed in it.

Types of fines

Criminal law also included monetary fines. The Slavs called them vira. Fines came to Rus' from Scandinavian law. It was vira that over time completely replaced blood feud as a measure of punishment for crime. It was measured differently, depending on the nobility of the person and the severity of the offense committed. An analogue of the Russian vira was wergeld. This was a monetary penalty, prescribed in the barbaric truths of the Germanic tribes.

Under Yaroslav, vira was a fine solely for the murder of a man who was a free man (that is, not a slave). For a simple peasant the fine was 40 hryvnia. If the victim was a person who was in the service of the prince, then the penalty was doubled.

If a free man was seriously injured or a woman was killed, the perpetrator had to pay half-virya. That is, the price fell by half - to 20 hryvnia. Less serious crimes, such as theft, were punishable by small fines, which were determined individually by the court.

Headhunting, flow and plunder

At the same time, a definition of golovnichestvo appeared in Russian criminal law. This was a ransom money that the killer had to provide to the family of the deceased. The size was determined by the status of the victim. Thus, the additional fine to the relatives of the slave was only 5 hryvnia.

Flow and plunder are another type of punishment that was introduced by Russian Truth. The state's right to punish a criminal was supplemented by the expulsion of the offender and confiscation of property. He could also be sent into slavery. At the same time, the property was looted (hence the name). The punishment varied depending on the era. Flow and plunder were assigned to those guilty of robbery or arson. These were considered to be the most serious crimes.

Social structure of society

Society was divided into several categories. The legal status of the population according to Russian Pravda completely depended on its The highest stratum was considered to be the nobility. It was the prince and his senior warriors (boyars). At first, these were professional military men who were the mainstay of power. It was in the name of the prince that the trial was carried out. All fines for crimes also went to him. The servants of the prince and boyars (tiuns and ognishchans) also had a privileged position in society.

On the next step were free men. In Russian Pravda there was a special term for this status. The word “husband” corresponded to it. Free persons included junior warriors, fine collectors, as well as residents of the Novgorod land.

Dependent strata of society

According to Russian Truth, the worst legal position of the population was among dependent people. They were divided into several categories. Smerdas were dependent peasants (but with their own plots) working for the boyar. Slaves for life were called serfs. They had no property.

If a person took out a loan and did not have time to repay, then he fell into a special form of slavery. It was called purchasing. Such dependents became the property of the borrower until they paid off their debts.

The provisions of Russian Pravda also spoke about such an agreement as the Row. This was the name of the agreement under which people voluntarily entered the service of the feudal lord. They were called ryadovichi.

All these categories of residents were at the very bottom of the social ladder. This legal status of the population, according to Russian Truth, practically devalued the lives of addicts in the literal sense of the word. The penalties for killing such people were minimal.

In conclusion, we can say that society in Rus' was very different from the classical feudal model in Western Europe. In the Catholic states in the 11th century, the leading position was already occupied by large landowners, who often did not even pay attention to the central government. In Rus' things were different. The top of the Slavs was the prince's squad, which had access to the most expensive and valuable resources. The legal status of population groups according to Russian Truth made them the most influential people in the state. At the same time, a class of large landowners had not yet formed from them.

Private right

Among other things, Yaroslav's Russian Truth included articles on private law. For example, they stipulated the rights and privileges of the merchant class, which was the engine of trade and the economy.

The merchant could engage in usury, that is, give loans. The fine was also paid in the form of barter, such as food and groceries. Jews were actively involved in usury. In the 12th century, this led to numerous pogroms and outbreaks of anti-Semitism. It is known that when Vladimir Monomakh came to rule in Kyiv, he first of all tried to resolve the issue of Jewish borrowers.

Russian Truth, the history of which includes several editions, also touched upon issues of inheritance. The charter allowed free people to receive property under a paper will.

Court

A complete description of Russian Pravda cannot skip articles relating to procedural law. Criminal offenses were tried in the princely court. It was carried out by a specially appointed representative of the authorities. In some cases, they resorted to confrontation, when the two sides proved their case one-on-one. The procedure for collecting a fine from the debtor was also prescribed.

A person could go to court if something went missing. For example, this was often used by merchants who suffered from theft. If the loss was found within three days, then the person in whose possession it was found became a defendant in court. He had to justify himself and provide evidence of his innocence. Otherwise, a fine was paid.

Testimony in court

Witnesses could be present in court. Their testimony was called the Code. The same word denoted the procedure for searching for lost items. If she took the proceedings outside the city or community, then the last suspect was recognized as the thief. He had the right to clear his name. To do this, he could carry out the investigation himself and find the person who committed the theft. If he failed, then it was he who was fined.

Witnesses were divided into two types. Vidoki are people who saw with their own eyes a crime that was committed (murder, theft, etc.). Hearsay - witnesses who reported unverified rumors in their testimony.

If it was not possible to find any crimes, then they resorted to the last resort. It was an oath by kissing the cross, when a person gave his testimony in court not only before the princely authority, but also before God.

A water test was also used. This was a form of divine judgment, when testimony was tested for truth by removing the ring from boiling water. If the defendant could not do this, he was found guilty. In Western Europe, this practice was called ordeals. People believed that God would not allow a conscientious person to get hurt.